Property Rights and Conservation

By: John A. Baden, Ph.D.Posted on May 21, 2014 FREE Insights Topics:

Minorities suffer abuses when their rights to property and person are violated. We examined historical situations involving Jews and Mormons in two recent FREE Insights (May 7 and 14). The underlying logic is clear: If people's property is not given legal protection, then it is cheap and easy to violate their persons and strip their possessions. Once considered, the importance of clear and enforced property rights becomes compellingly obvious.

Let's now consider the positive contributions of property rights to conservation goals. I'll suggest how and explain why clear property rights can foster a constructive mix of environmental quality and economic progress. Alas, few Greens have yet to demonstrate understanding of these potentials. We will again use an historical case, the management of the Audubon Society's Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary in Vermilion Parish in coastal Louisiana.

Let's define the terrain we'll explore. I find it useful to divide environmental policy into two parts. First is pollution, nasty stuff we want to avoid or minimize. It can injure or kill people and things about which people care, clean water for example. I label that category sludge. The second field involves parks, wildlands, and wildlife. These are places people love to visit. Yellowstone Park is an excellent example. This second category is the arena I prefer, romance.

These fields often overlap. Climate change is a huge case of overlapping sludge and romance. Air pollution for example, may harm polar and grizzly bears' long-term viability. Below we deal with constructive possibilities in the field of romance.

Federal and state governments own much of America’s “romance land”. This includes nearly all of our official "wilderness" and most of our natural parks. Wildlife, on the other hand, is rather different. The Nature Conversancy owns or protects about 15,000,000 acres, roughly seven times larger than Yellowstone Park. Ducks Unlimited (DU) manages a bit less, some 13,200,000, but "influences" another 100,000,000 acres through various contracts and agreements. Such influences include payments offered by DU to farmers to not take federal subsidies to destroy prairie potholes, some of North America's best breeding grounds for waterfowl. DU's total is just over half the land area managed by the U. S. Forest Service.

The Rainey Conservation Alliance is a coalition of landowners and land managers working together in southern Vermilion Parish, Louisiana. The alliance represents more than 170,000 contiguous acres of marsh, forested ridges, and beach habitats. It includes the National Audubon Society's Paul J. Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary, which Audubon has managed as a wildlife sanctuary since it was donated to the society in 1924.

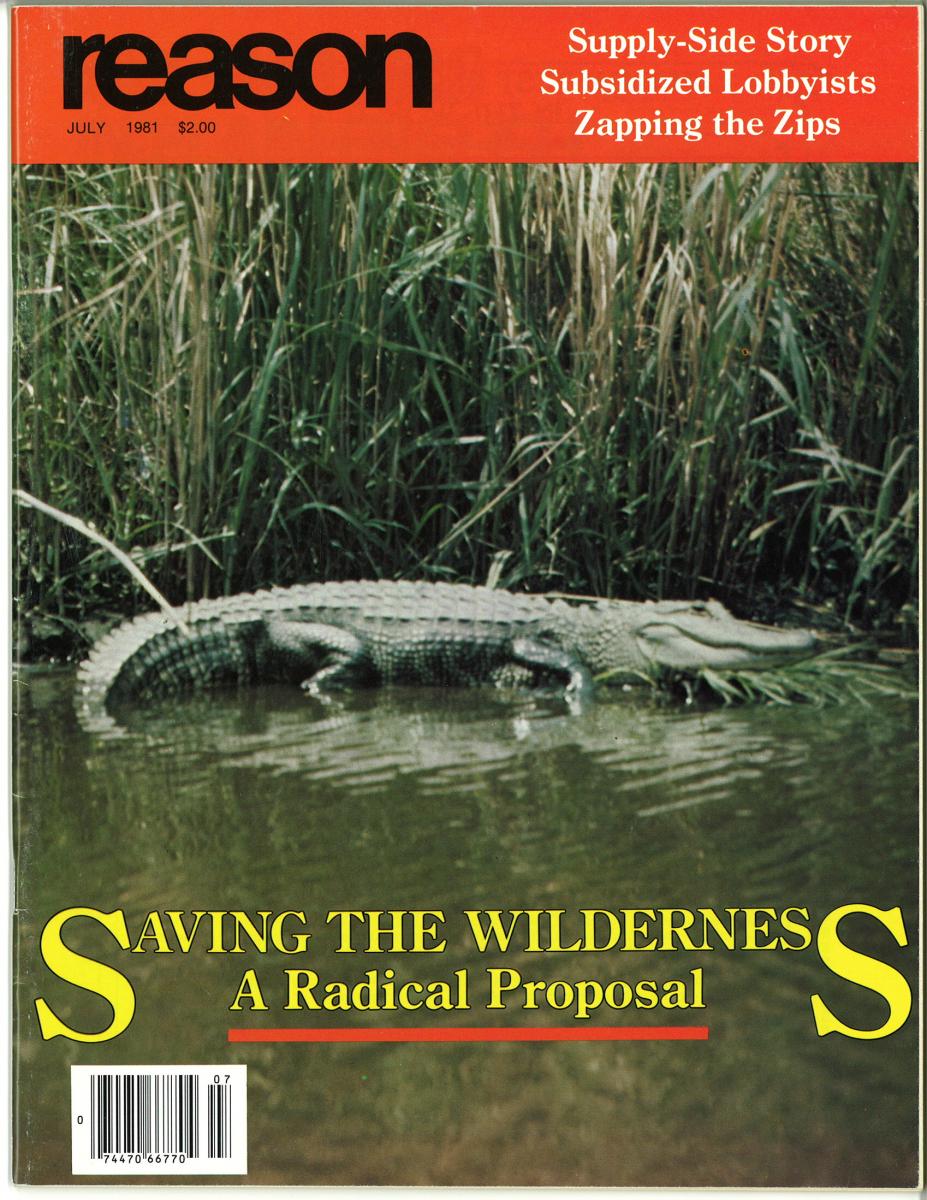

Over three decades ago (actually July, 1981) my MSU colleague, Rick Stroup, and I published the cover story in the libertarian magazine, Reason, "Saving the Wilderness: A Radical Proposal". This was a time where America and the rest of the developed world were "running out of everything". Concern about energy, strategic metal and mineral commodities were especially strong. We have never run out of oil, copper, or nickel, or any other strategic or pedestrian commodity. Still, few people have learned that scarcity has yet to win a race against creativity when property rights are secure and markets free to operate.

Concurrently with concern over scarcity, environmentalists were nearly unanimous in their belief that only government could manage for environmental quality. Few people had learned there is preferable arrangement: Governments are better monitors of and protectors from externalities than managers of lands and businesses.

Audubon's Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary, because it was privately held, found ways to create harmony among ecology, economy, and liberty. They were able to find constructive accommodation among these oft-competing objectives. Its wells produced energy while providing and protecting habitat.

Initially there seemed to be an inherent contradiction between preserving habitat at Rainey and developing its oil and gas. However, since Audubon owned the land and energy rights, it’s managers could determine if, how, and when any drilling took place. Audubon specified conditions to protect habitat and wildlife.

Audubon had the rights to refuse any and all bids to explore and produce gas and oil--but they would suffer the opportunities foregone if they refused every bid. And they had many excellent opportunities to use any funds they received to improve and protect existing and buy more wildlife habitat.

Meanwhile, the energy exploration and production (E&P) companies had incentives to discover and act in ecologically sensitive ways. When dealing with Audubon they faced opportunities to bid on both ecological and financial margins. Here is the key point--clear property rights gave both parties incentives to cooperate. That way both conservation and corporate interests were served.

An Audubon pamphlet of that period speaks calmly of the situation: "There are oil wells in Rainey which are a potential source of pollution, yet Audubon experience in the past few decades indicates that oil can be extracted without measurable damage to the marsh. Extra precautions to prevent pollution have proven effective."

This calm description of the energy development at Rainey is refreshing and encouraging. Lonnie Lege, the manager of Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary, spoke quite fondly of their improved capacity to sustain wildlife:

After they've finished their drilling and they still have their equipment, if we need a job done with a drag line, they're usually happy to do it. So we have had some levees constructed and flumes installed so that we have water control that we could not have afforded if we would have had to pay for it. They was real cooperative.

Decisions in the field of environmental romance, as everywhere else, are based on information and incentives. Who holds the property rights has a dramatic influence on both the amount and quality of information generated and the incentive to act upon it. When Audubon owns the rights it can set the terms of access for exploration and production. Knowing this, the energy companies promise environmentally sensitive work. The renewal of the lease is contingent upon keeping these promises. In this context neither party has incentives to invest in lobbying or renting congressmen.

The lack of clear property rights explains why, in 1981, when writing the original Reason article, we learned some of the funds Audubon received from Rainey were used to lobby against energy exploration and production in Montana's Rocky Mountain Front. And this isn't simple hypocrisy: Audubon couldn't set conditions in that oil patch. Since they lacked control over exploration and production, the conservative decision was to use political pressure to oppose energy exploration on the Rocky Mountain Front.

But even the best arrangements are not fool proof. Here is the most fundamental ecological law: Nature bats last. Hurricane Rita hit Louisiana in 2005. The 26,000-acre (40 square mile) Rainey Sanctuary lost several hundred acres of marshland habitat and continues to suffer damage. "It's getting to the point where there is so much damage, and it just costs so much money to contain the damage," said G. Paul Kemp, director of Audubon's Gulf Coast Initiative. "We know we're fighting a losing battle."

Two key changes occurred between 1981 and Hurricane Rita: The original leases with the oil companies expired in the 1990s, and the management of Audubon changed. The new management didn’t take into account the positive precedent Audubon had set in the original lease negotiations. They were also more sensitive to environmental dogma; they had learned the Green catechism. However, Audubon had property rights to the energy potential and trustees had responsibilities to advance the Rainey Sanctuary's mission, fostering wildlife through habitat protection. The amount of revenue today’s oil is $102/barrel contrasted to the $12-$20 per barrel royalty in the 1990s.

And the Rainey managers are creative. To achieve "the sanctuary's sole objective of conserving bird habitat, Audubon uses (cattle) grazing as a tool to accomplish the desired diversity of plants, animals, and natural communities" (Forest Service: Barriers to Generating Revenue Or Reducing Costs, Appendix VII, Marcus R. Clark, June 1, 1998).

Jen DeGregorio in Times-Picayune reported in 2010:

...Audubon is considering a measure that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago: opening the sanctuary to oil and gas drilling. Profits would be used to pay for marsh restoration, multimillion-dollar land-building projects that Audubon cannot now afford. Audubon officials have been quietly debating the proposition for months, knowing the matter is sure to stir controversy. Oil and gas drilling is anathema to the environmental community, and even Audubon has publicly opposed tapping Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

"This is actually quite an interesting opportunity for both conservationists and the oil industry to see if development can be done differently and if it can be done economically and in a way that protects the environment," said Denise Reed, a coastal scientist at the University of New Orleans, of Audubon's proposal.

When considering lease renewals, Audubon again tapped consultants to evaluate drilling in the marsh. Meanwhile, state regulators, by contrast, consider oil and gas extraction as a given, issuing hundreds of permits each year to drill in the coastal zone.

There are strong incentives to produce oil and gas. As a result, "These remaining wetlands are incredibly important to about 36 species of birds that are in decline. Their populations are diminishing because of habitat destruction everywhere," Kemp said. "There's no way of stopping the development of oil and gas out here. A lease gives us some ability to control things."

Active oil and gas fields, both on land and out in the Gulf of Mexico, surround Rainey. ExxonMobil owns nearly 150,000 acres, and private holders lease their land to many energy firms. There are nearly 5,000 gas wells in Vermillion Parish.

The reasons landowners lease to oil companies are obvious, they make money. Nationally, landowners receive on average just over 18% of the value of oil produced by a well. Federal law requires lease payments be at least 12.5% of value of gas and oil produced. Of course the companies' accountants, engineers, and lawyers design the contracts and measure production. Hence, landowners are often slighted, but incentives to produce gas and oil remain high.

This is a highly complex situation but some things are clear. First, more of this sensitive marshland will be developed. Second, government monitoring of and protection from externalities is important--and in a positive way. Third, there is a potential for environmental entrepreneurs to build upon Audubon's Rainey experiences. Here is one possibility. It is inspired by conservation easements held by land trusts.

American land trusts are nonprofit corporations, usually 501 c-3s. They rarely own land but rather hold the development rights to land with conservation or wildlife values. When acquiring land with a conservation easement (CE) the land trust accepts responsibility to monitor that land and has trained professionals to do so.

When land is put under a CE, specified developments are precluded. A farm or ranch, for example, will continue to be operated for commercial agriculture and recreation but cannot be broken into ten-acre "ranchettes". The land is to be maintained in agriculture: It provides habitat, open-space, recreation, and view-shed.

The legal classification as CE land reduces its appraised value, sometimes a great deal. The simple reason is that options are foregone: The land cannot be transferred to the highest use as measured by market prices. A thousand acre ranch near Bozeman, Montana or Jackson, Wyoming that can be subdivided into 100 ten-acre ranchettes fetches more on the market than one that must remain intact and not be developed or subdivided. But all is not lost. Here is the logic.

Assume a piece of land diminishes in appraised value by $1,000,000 when placed in a CE. When the landowner places her land in a CE she can feel good--and take a charitable deduction when filing her taxes for these trusts are public charities, 501 c-3s. She has given something of value, the development rights, to a land trust.

Now imagine a new type of CE for lands with gas and oil potential. This CE would require that E&P be conducted in an environmentally sensitive manner, much as any production on the Rainey Sanctuary. Here is some of the law under which this type of CE could work.

Federal Tax Coordinator 2d ¶K-3509. Natural habitat preservation under the qualified conservation contribution rules.

A "qualified conservation contribution." is a contribution of a qualified real property interest to a qualified organization exclusively for conservation purposes, see ¶ K-3500 et seq.

For these purposes, "conservation purpose" (¶ K-3507) includes the protection of a relatively natural habitat in which a fish, wildlife, plant community, or similar ecosystem normally lives. 35

"Habitat" means the area or environment where an organism or ecological community normally lives or occurs. "Community" means a group of plants and animals living and interacting with one another in a specific region under relatively similar environmental conditions. 35.1

....

The relatively natural habitat must be significant. For example, the alteration by human activity of the habitat or environment by a man-made dam won't cause the deduction for the contribution to be disallowed if fish, wildlife, or plants continue to exist in it in a relatively natural state. 36

Such CEs would increase the burden imposed on exploration and production and hence reduce the royalty received. The difference would be a charitable contribution to the new land trust. A certified appraiser would determine this spread of values, those before and after the CE. It is highly likely that with experience the energy producing firms would become ever better and more efficient at meeting conservation requirements. And they would compete to do so.

The creation of the new type of CE would be an exercise of environmental entrepreneurship. It would require clear and transferable property rights. These are important ingredients of sustainable ecosystems, especially when nature bats last and we can't predict where she will hit.