The Glorious Experiment of Yellowstone Park

By: John A. Baden, Ph.D.Posted on February 25, 2016 FREE Insights

Americans are celebrating the Centennial of the U. S. Park Service. Its creation is one of the most successful experiments of Progressive Era reformers.

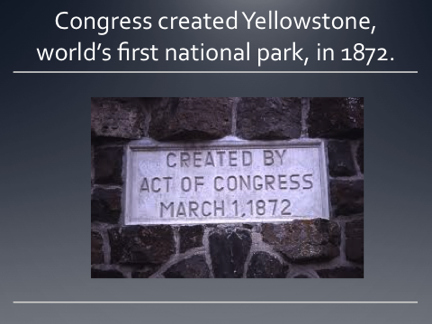

They created Yellowstone, the world's first national park, in 1872. It stands out as a truly great and largely successful experiment in ecological and social management.

Yellowstone Park was a creative invention with preservation goals. What arrangements are most likely to preserve Yellowstone's qualities and character? As serious new threats unfold, inescapable dangers to Yellowstone and other parks arise in ecological, economic, cultural, and demographic forms.

The creators could not know exactly how to achieve these goals and the Yellowstone experiment goes on. Managers adapt to its dynamic political, cultural, and economic environments. They cannot stand athwart history and cry "stop!"

Fundamental disagreements about management policies are normal. The current conflicts over bison exemplify these conflicts.They are scientifically complex, contentious, and packed with heavy emotional baggage. In this way they resemble earlier issues involving elk and wolves.

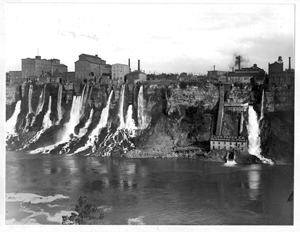

However emotional the disagreements, the overwhelming majority of people who elect to live here treasure the Park. It's creation preserved a magical place from the crass commercial exploitation that characterized America in the post-Civil War, robber baron period. The Progressive Era conservationists learned the importance of preservation from the example of Niagara Falls.

f.n. (The crony capitalism that characterized post Civil War America has returned during recent decades. Political and economic elites again use governmental power as an engine of plunder. That is the behavior to expect when politicians become stationary bandits. This outcome was a great fear of America's founders, one they designed our constitution to prevent.)

During post Civil War decades American citizens resembled those of emerging nations today. They were poor people with short life expectancies and strong ambitions for improving their material lives. In this context desires for increased prosperity naturally trumps ecology.

Yellowstone was created as an environmental sanctuary, one deserving and needing protection. And it still does. New financial, social, demographic, and ecological challenges threaten the parks, even Yellowstone. Each challenge develops special interests that evolve into political constituencies. Given this certainty, what arrangements are most likely to preserve Yellowstone's qualities and character?

Let’s consider historical challenges in Yellowstone.

Yellowstone had been protected by ignorance of its existence, disbelief in its alleged attractions, and its remote location. Also, in 1872 America was in a lightly populated nation. It held only 42 million people, less than a dozen per square mile.

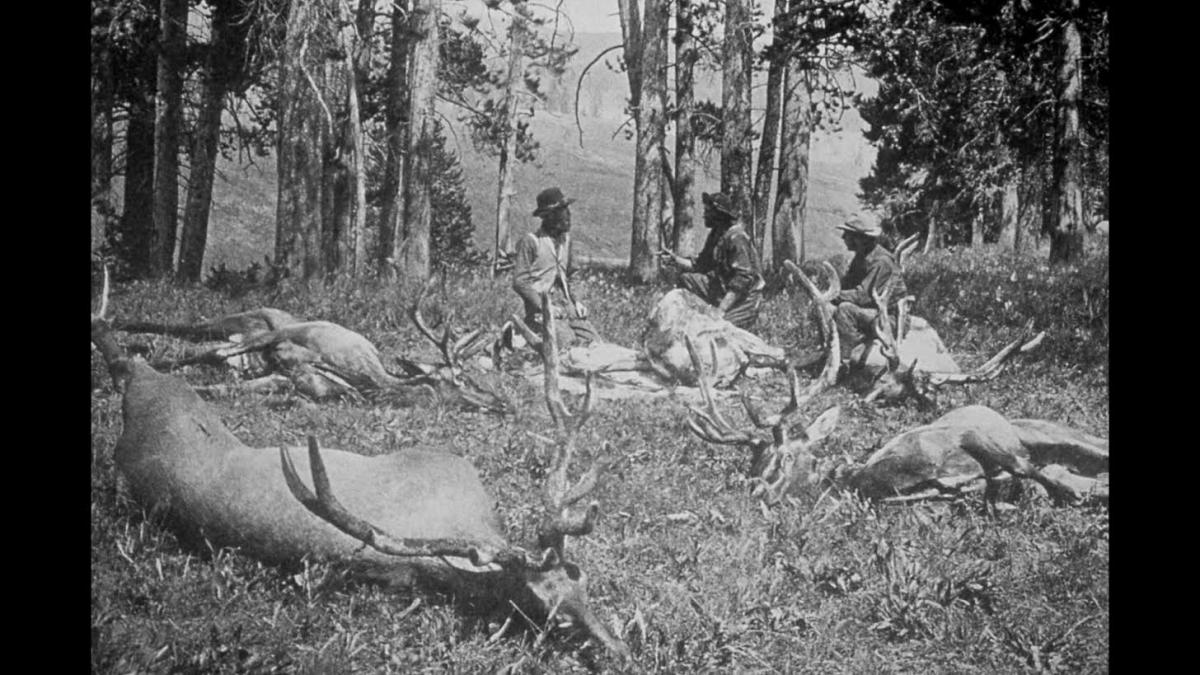

Yellowstone came to the nation's attention when it became a national park. It was a commons open to all during its first dozen plus years. Exploitation predictably followed. Some years poachers shot thousands of elk, fish and timber were often illegally taken, as were geological specimens.

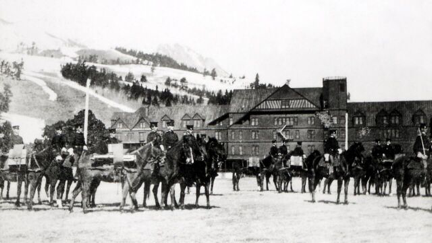

In 1886, the U.S. Army was assigned protective duties for the Park. In 1891 it established Fort Yellowstone. It remains the Park headquarters today.

Fort Yellowstone grounds, 1910

World traveler and lecturer, John Stoddard was educated at Williams College and Yale Divinity School. He toured and photographed the Park in the 1890s and observed: "No one who has visited the National Park ever doubts the necessity of having soldiers there....". (f.n. Explorations in Greater Yellowstone, p. iii, original Lectures ms., vol. 10, p.216.) But today they aren't--excepting on vacation. (The Park gives active duty military free admissions.)

Congress created the U. S. Park Service in 1916 and it took over Yellowstone Park from the Army in 1918. This began our experiment in park management under the "scientific management" philosophy.

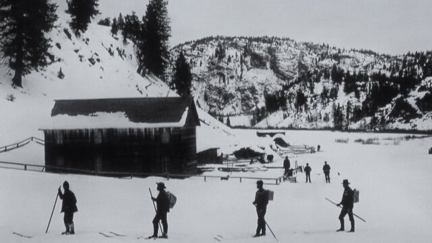

U.S. Army leaving Yellowstone

This system was intended to provide management by scientifically trained, honorable men dedicated to the public interest and insulated from politics. This provided significant but imperfect improvements over alternatives. In particular, this system of federal ownership and management surely constrained rampant and shortsighted commercial development.

The "scientific management" phase of America's national park experiment marked significant progress. It encouraged sound ecological and economic management. It was not, however, immune to the pathologies inherent to command and control via federal force. There are two fundamental problems of science and politics.

First, park ecology involves many complex species and a huge number of time and place specific variables affecting their interactions. Hence, park managers and scientists sometime simply do not fully understand the system and make errors. Yellowstone examples include extinguishing all fires ASAP, exterminating all wolves, and all Park hotels feeding food scraps to bears.

Putting out small fires meant continual fuel buildup. Exterminating wolves led to huge increased in elk numbers with resultant habitat degradation. In the bear example, park garbage dumps became popular entertainment for visitors, a sure place to see grizzly bears. Bears lost fear of people, posed danger, and were dispatched.

Such results are predictable consequences of the Progressive Era's experiments with "scientific management" of America's parks and natural resources. Each of the poor policies and practices became well established. All developed political constituencies within and around Yellowstone. Of course hotels liked to boast of the certainty of their guests seeing grizzlies feed. Critics inside and outside the Park were, or feared they would be, shut out as grizzly bear biologists John and Frank Craighead famously were.

Managing park ecosystems is difficult but the law is clear: The Park Service must protect park ecosystems. First protect the resources and then provide for public enjoyment. This is the ideal. However, the natural exercise of Congress is benefitting constituencies. The Park Service, knowing that Congress sets its budge, ultimately yields to Congress. This is how the ideal and the actual diverge. The major causes are consituency driven political interference and career building and protection in the agency.

The Park Service initially managed 15 national parks and 20 monuments. Responding in large part to pressures from local boosters, there are now 400 units in the system. Some receive only a few thousand visitors each year and cost the Park Service hundreds of dollars per visitor. Naturally, within the Park Service these costly additions compete for operating and maintenance budgets. (f.n. the Frederick Law Olmstead Site in Massachusetts. It receives fewer than 5,000 visitors a year but has an annual budget of $2.4 million, nearly $500 per visitor.Budget Justifications and Performance Information: National Park Service, Fiscal Year 2012," 2011, pp. ONPS-189–190, ONPS-207.) The GAO reported unfunded repairs and maintenance to be $12,000,000,000 in 2016. (This includes 25% overhead the Park Service charges on construction projects.)

(f.n. This high figure exists due to strategic reporting by park managers, they want the highest justifiable numbers. Also, federal rules and payoffs to organized interests drive up costs. For example economist Randal O'Toole states that "The Park Service spends double per square foot on housing compared to private home construction costs and double per square foot on visitor centers vs. private commercial construction costs.")

Since sound ecosystem management rarely provides good pork barrel, Congressional pressures usually harm the resource.

In sum, most of the internal threats and some of the external ones, result from Congressional meddling in park management. Insufficient funding is another problem and one certain to worsen.

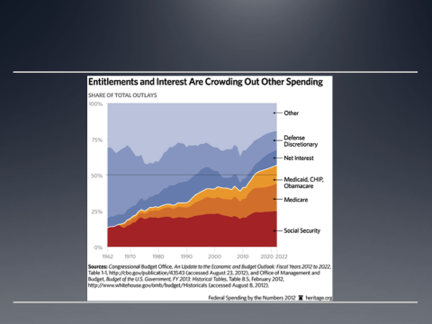

The entire Park Service budget is at Congressional discretion. In contrast, programs such as Medicare and Social Security are locked in by formula. In the political arena entitlements trump ecology and welfare wins over wildlife. Then consider the specter of climate change.

If the climate warms and oceans rise, major cities including New York, Miami, and Baltimore will be at risk. Opportunistic political actors will tout the trillions of real-estate dollars and million of lives at risk. There will be new, and to some people, persuasive funding demands competing for Park Service funding. If funds are allocated by the political process, then entitlements trump ecology and and welfare beats wilderness. Among people who understand this process a key conservation goal for the 21st century is to insulate the parks from politics. Public trusts such as those managing Mount Vernon and Monticello stayed open when the federal government shut down the national (read political) parks in 2013.

The creation of the national parks was surely a glorious and worthwhile experiment.

We've learned a great deal and made many adjustments since the Yellowstone Park experiment began in 1872. I suggest that the next effort be to understand and promote the understanding of why "public" need not mean government owned and operated. We have had hundreds of years of experience with public trusts. They are not perfect to, no institution is, but trusts generate funds and insulate the founding purpose from politics. I suggest the next experiment be a national public trust for managing Yellowstone. It would remain the world's first national park but be well insulated from politics. This could also become the world model for park and wildlands management. Yellowstone would continue its role as the world's leader.